Original Article: Click Here

San Diego County residents should expect to pay a lot more for water in the near future.

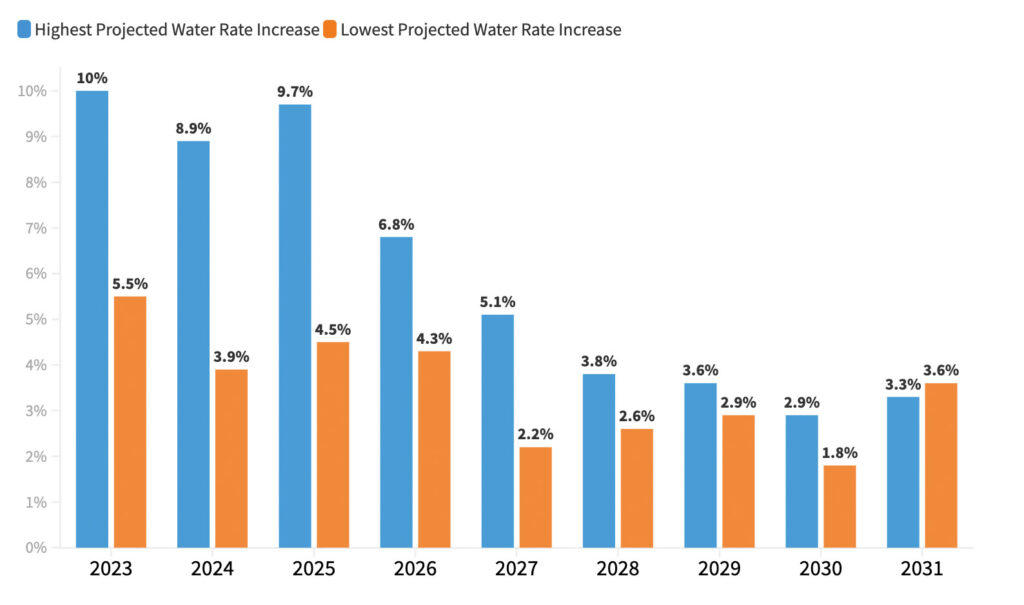

The San Diego County Water Authority, which controls most of the region’s water resources from the drought-stressed Colorado River, is predicting anywhere from a 5.5 to 10 percent increase in the cost of water beginning in 2023, with hefty hikes continuing in the years thereafter.

The agency pointed to multiple drivers, chief among them an expected drop in demand as more cities build water recycling projects and the Los Angeles-based Metropolitan Water Authority, which controls San Diego’s access to the Colorado River, continues raising its rates.

But that’s only part of the story. The city of San Diego, the San Diego County Water Authority’s biggest customer, which already pays some of the highest water rates in the country, is challenging the way the agency manages its billions in debt and pays for the stuff it builds — even calling for third-party audits of its financial plans.

“It is … incredibly important to the city that every rate driver be thoroughly analyzed to ensure rates are not escalating to a more unaffordable point on behalf of San Diegans,” Jay Goldstone, San Diego’s chief operating officer, wrote to Water Authority General Manager Sandy Kerl in a Sept. 15 letter.

How Much Water Rates Could Rise Over 10 Years

The cost of water is going up. The San Diego County Water authority is forecasting annual water rate increases between 5.5 and 10 percent for ten years beginning in 2023, with hefty increases continuing in the years thereafter.

The Water Authority stressed these ranges are just guidance and the actual rates are set each year under a different budget process.

But the forecasted increases gave some Water Authority’s customers sticker shock.

When Water Authority raises prices, the costs to its customers shake out differently based on their own calculations. For instance, a 3.6 percent bump in cost from the Water Authority next year triggered a 7 percent bump for Olivenhain Municipal Water District customers (which serves an area from Carlsbad to the 15, Fairbanks Ranch and Cardiff).

“The impact to my agency is actually double,” Thorner wrote in an email. “It is very hard to convey that message to my customers of the true wholesale water rate pressures that my agency is having to manage.”

The average monthly water bill for someone living in the Olivenhain water district in 2017 was about $70, according to a recent survey of water bills by the Otay Water District. It’ll be about $91 a month next year. It’s a similar story for San Diegans who paid about $77 a month in 2017 and will pay about $90 a month next year.

The city of San Diego is especially worried about the highest rate increases rolling in before 2025 because that’s when the city will start paying off loans it took out to build Pure Water, a multi-billion wastewater-to-drinking water project. Those loan payments will also require raising rates on San Diego residents and businesses.

“We’re looking at two significant drivers of increased costs that will overlap, essentially a double whammy to the City’s water customers” said Matt Vespi, the city’s chief financial officer.

This problem illustrates a big theme in California water politics. The Water Authority spent a lot to get water here and keep it here. While water is a public resource, it’s still treated like a business in that the public agencies who control it depend on the revenue they get from selling it.

But now people are using less of it and cities are starting to recycle more of it, meaning the Water Authority can expect to sell less of the water they’ve already paid to bring here. (The Water Authority sold 11 percent less than they banked on in the last two years, according to the agency’s latest financial activity report.)

They make up their costs by raising prices.

Once Pure Water is built, the city of San Diego won’t have to buy as much water from the Water Authority — the project, it’s estimated, will provide about half the city’s drinking water. While that could result in lower rates for San Diegans eventually, that’s also going to have an impact on the Water Authority’s bottom line in the future. And that’s worrisome because the Water Authority still has about $2 billion in debt to pay off, plus all the other expenses of buying water itself and maintaining and operating its water infrastructure.

That the Water Authority has plenty of water to sell, but not enough buyers, is becoming a harder fact to ignore. Even credit rating agencies are starting to notice.

In Spring, S&P Global gave the Water Authority a “negative” outlook on its financial future (changing the designation from “stable”) citing declining water sales and local water recycling projects like Pure Water.

“Affordability is already a credit vulnerability for the authority as its existing rates are elevated relative to those of its regional and national peers,” S&P Global wrote in March.

Moody’s and Fitch, the other major credit ratings agencies, felt the Water Authority was still on stable financial ground, but cited similar concerns, including an effort by two of 24 agencies to ditch buying from the Water Authority altogether.

How credit rating agencies view the Water Authority’s financial stability is yet another stressor on future water rates, the agency’s budget analysts say.

Public agencies usually get the highest credit ratings, meaning they can borrow a lot of money at a low interest rate. They are low-risk borrowers because they have a dependable stream of cash: the taxpayer or, in this case, the ratepayer. When a credit rating agency downgrades a rating, it signals concern about the financial state of the public agency, which can force the agency to borrow at a higher interest rate — costing ratepayers down the line.

“From my perspective, there’s significant risk to a downgrade,” said Lisa Marie Harris, the Water Authority’s director of finance, at the Aug. 26 board meeting.

Avoiding that is part of the Water Authority’s strategy with its financial plan. At least in part to appease rating agencies, the Water Authority wants to take out less debt in the first place.

To do that, the Water Authority’s board of directors needs to change a policy. The agency wants to pay for capital projects (otherwise known as stuff the agency wants to build) with about 65 percent cash and 35 percent debt, which is basically the opposite of the policy in place now. Typically, the way to raise cash is by raising rates.

That’s a red flag for the city of San Diego, which won’t be buying as much water from the Water Authority once Pure Water comes online. But if the policy changes, its residents will have to pay more now for its water, in the form of cash payments made possible through increased rates.

“It’s an intergenerational equity concern,” said Ally Berenter, senior manager of external affairs and water policy for Mayor Todd Gloria’s office. “Debt financing more equitably distributes rate impacts for capital improvement investment” than cash.

What she means is that borrowing money (going into debt) to pay for water infrastructure spreads out big costs slowly, across generations of ratepayers, instead of asking today’s ratepayers to pay for a bunch of stuff right now through cash.

The Water Authority would argue the opposite. In their view, paying more cash up front means current customers are contributing to the cost of the water infrastructure they’re benefitting from — instead of saddling future generations with more debt, according to a Sept. 9 presentation the agency gave the city of San Diego.

Not everyone is upset with this financial plan, however. In an email, Tenille Otero, a spokeswoman for the Otay Water District, whose representative currently chairs the Water Authority’s board, called the long-range financing plan “responsible planning” that ensures the region has a reliable water source. Otay expects to raise rates about 3 percent per year under the Water Authority’s plan.

In the meantime, the city of San Diego is pressing the Water Authority to slow down its quest for cash and start monitoring its cash-to-debt ratios more closely, on a biannual basis instead of every five years, when the agency does a long-range financial plan. San Diego also wants a third-party to audit the Water Authority’s financials so member agencies have a better idea what kind of rate increases might be coming down the line.

“We want to increase transparency and a better road map going forward with the changing landscape of the industry of wholesale water,” Vespi said.